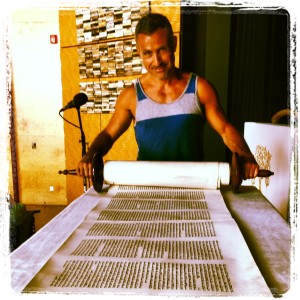

This is my sermon from the Rosh HaShanah evening service at Congregation B’nai Olam in Fire Island Pines, NY. I’m posting it here by request, with thanks to my readers and editors, to those who provided inspiration, and to those who listened to it with open minds and hearts.

It was finally time. Shlomo and his husband Shimi had been planning this trip for so long. And they both really needed a vacation. The day of the trip, they were so excited they could hardly wait to board the ship.

It was finally time. Shlomo and his husband Shimi had been planning this trip for so long. And they both really needed a vacation. The day of the trip, they were so excited they could hardly wait to board the ship.

They got to the port easily and boarded. Everything was going well – the sun was shining, the water was a sparkly blue, the seats were comfortable, the view was spectacular.

Shlomo leaned back against Shimi and smiled. “This is so lovely,” he said. “Thanks for making this happen.”

And Shimi smiled back. “It will be so nice to relax for a while.”

They were far out at sea when Shlomo looked over at a man across from him. At first he thought he was seeing things, but then he realized, no, the man across from him indeed had a drill. And he was drilling a hole beneath his seat.

Shlomo leapt up and called out, “Hey, what are you doing?”

The man turned to Shlomo and said, “Don’t worry, I’m only drilling under my own seat, not yours.”

Shimi saw what was going on, and jumped up too. “Please, don’t do that!”

The man ignored them and kept at it.

“Stop that right now!” Shlomo yelled.

The man turned to Shlomo and Shimi. “What business is it of yours what I do to my seat?” he asked.

“Please stop,” Shlomo pleaded.

Again the man brushed him off. “I like to see the water underneath me when I travel. What do you care? I’m not touching your seats.”

Shlomo turned to Shimi. “What should I do?” he whispered. “I want us to have a nice vacation.”

“I know,” Shimi whispered back. “But we have to get him to stop.”

So again Shlomo tried to stop the man. “What you’re doing makes no sense. It’s dangerous.”

The man still went on drilling. “Stay out of my affairs!” he yelled at Shlomo and Shimi. “This is my seat, I paid for it, and I have the right to do what I want to it!”

Again, Shlomo and Shimi exchanged looks.

“Sir, you must stop right now!” Shlomo said.

The man looked up. “Go enjoy your vacation. Go find other seats. Go do whatever you want, but mind your own business. Why can’t you leave me alone?”

“But don’t you realize,” Shlomo asked, “That if you drill under your own seat, the water will rise up through the hole and flood the whole boat. What you’re doing endangers us all.”

(adapted from Midrash Rabbah, Lev 4:6)

This ancient Jewish story comes to us from the midrash – with a little modern spin of course. But I didn’t choose it just to share a sweet Jewish folktale – there’s something profound embedded in this story.

Jews have long understood that we’re all in this together. We understand that the hole under your seat in the boat will sink us all. Over and over, throughout the Torah, we are told to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, and care for the orphans and widows. Thirty-six different times the Torah tell us to love the stranger, for we were strangers in the land of Egypt. In the context of the time it was written, the Torah teaches that everyone in a society is bound up together, that the fate of some is the fate of all, and that the powerful have a responsibility to help the powerless. Our sages understood that when one suffers, we all suffer.

Another story. It’s a Friday night at the synagogue. An angry mob marches by. The synagogue calls the police and asks for protection, but are turned down. The police have their hands full and protecting the synagogue doesn’t really seem like a big deal given what else is going on. But as this mob marches past the synagogue, they chant “the Jews will not replace us” and “blood and soil.” They threaten to burn down the synagogue. That evening the synagogue goes on lock down until they can safely get everyone out the building. Thinking the worst is over, on Saturday morning the congregation gathers again for services – there’s a bar mitzvah. And meanwhile, armed militants carrying swastikas on flags march around the building yelling “Sieg Heil.” And more of the chants of the night before – “Jews will not replace us.” “Blood and soil.” And as the mob outside swells in numbers, the synagogue chooses to quietly, carefully, take the Torahs out the back door and drive them away to safety. Havdalah services are cancelled because they decide it is too risky for Jews to gather together. This story is not from Germany, circa 1937. This happened a few weeks ago, in Charlottesville, Virginia. This story happened in 2017, here, in this country, land of the free and home of the brave.[i]

I’m not an alarmist. In my almost 20 years as a rabbi I have never given a sermon about antisemitism. But things have changed so much since we were together here a year ago. I never in my life thought something like what happened in Charlottesville could ever happen again, and certainly not in this country. And yet what was unimaginable a year ago has happened.

Antisemitism is alive and well in an America in which racism and bigotry are becoming more and more mainstream and normalized. Along with the national rise in hate crimes, this past year has seen there has been a tremendous rise in antisemitic incidents in schools, playgrounds, cemeteries, and synagogues across America. Suddenly it’s become clear that we’re in the boat too, that this boat is surrounded by racists and misogynists and homophobes and transphobes and science-deniers and white supremacists and the KKK and antisemites, and that it’s taking on water. And we have a choice to make about how we’re going to respond.

It’s not that I didn’t know antisemitism existed. But I naively felt that, for the most part, at least in the United States, antisemitism was part of history. Unlike the world into which our parents or grandparents or great-grandparents were born, as Jews most of us experience tremendous privilege and great opportunities. I’m not saying that everything about our lives is good and easy – not at all – but it’s probably fair to say that for most of us, being Jewish has not been the thing that’s gotten in the way.

I didn’t raise my children to be afraid as Jews and I didn’t raise them to define their Jewish identities in relationship to anti-Semitism. That is, as a rabbi, as a Jew, as a mother, I’ve always felt strongly that Jewish identity should be based on pride in Jewish values and history and accomplishments, in the enjoyment of living a Jewish life of holidays and rituals and yes, good food, and not as a response to the ugly reality of anti-Semitism.

Jewish identity should be about joy, about love, about pride – about how the foundational values and customs of Judaism enhance our lives and give it meaning, not about how we’re hated, not about our suffering. “Because they hate us” is not a good enough reason to be Jewish. We should be proud to be Jewish for the positive reasons: because being Jewish brings us joy, because it brings meaning and purpose to our lives, because we love the music or the sacred texts or the food or the jokes or the culture of study and question-asking or the tradition of storytelling or the drive to make the world a better place.

I put it to you that in these precarious times, just to be proudly Jewish is a form of protest. In this new year, even as we work to keep the ship from sinking, fight antisemitism on a personal level by owning your Judaism, by taking pride in it, by being a Jew publicly. Even as we work to help others stay afloat, find a reason and a new way to claim your Jewish identity. Even as we reach out a hand to the drowning, use core Jewish values as a way to frame the choices you make in your life. For that too is a form of resistance.

But these steps are not the end of what it means to own our Jewish identity.

That day in Charlottesville tore the lid off the quiet contagion of anti-Semitism in America that had been festering in the dark. Anti-Semitism doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Where’s the antisemitism, there’s white supremacy, racism, homophobia, and bigotry of all kinds.

When rights are taken away from anyone, they’re taken away from everyone.

When hate is allowed to flourish, it pollutes us all.

Intolerance and hate and the deliberate diminishing of equality under the law are infections that threaten the freedom of us all.

There can be no moral equivalency when it comes to hate and its accompanying violence – it is simply wrong and must be condemned. When a moral equivalence is made about groups whose mission is hate and intolerance and exclusion, and those who protest such groups, we are all harmed. There is no excuse and no context that makes that kind of comparison acceptable in a democracy founded on the principles of equal rights for all.

Even as we respond to antisemitism by living our Judaism out loud and without fear, we must also find common ground with others who find themselves on the receiving end of hate, racism, and suspicion, even if we don’t completely agree with their outlook or values. It is our responsibility to remember that there are people with fewer resources than we have, and less recourse than we do, who rights are threatened or being taken away. Our tradition is clear:

Im ain ani li, mi li? If I am not for myself, who will be for me? – We must speak up for ourselves.

And if I am only for myself, what am I? – But we can’t only be for ourselves. We have a responsibility to help others.

So in this new year, it is time for us to show up for others as we also commit to showing up and speaking up for ourselves. As we enter this annual period of reflection and self-examination, we must ask: How can I fight antisemitism by taking pride in being a Jew? Or, because I know we have many beloved participants here who aren’t Jewish, what role can you play in eradicating this disease of anti-Semitism? But it doesn’t stop there. Because we know what it is to be hated, to be feared, to be oppressed, to be a stranger, and because Judaism demands of us that we respond with compassion and justice, we must go on to ask: what more can I do to fight hate and intolerance against all people? What role can I play in speaking up for the powerless or voiceless? If not us, then who? And if not now, when?

[i] https://reformjudaism.org/blog/2017/08/24/you-think-it-couldnt-happen-your-synagogue-so-did-i