My mother emailed me yesterday, nostalgic about Passovers past. She had opened a cookbook to begin her prep, and in it found a recipe card written in my grandmother’s handwriting for Pesach mandelbrot.

My mother emailed me yesterday, nostalgic about Passovers past. She had opened a cookbook to begin her prep, and in it found a recipe card written in my grandmother’s handwriting for Pesach mandelbrot.

I’ve always loved Passover but the truth is, with one exception, I don’t have memories of my grandmother’s cooking. That’s probably because she wasn’t a great cook. Far from the stereotypical Jewish grandmother, she was a professional woman who had little interest in homemaking. And though my mother is a great cook who makes terrific vegetarian tzimmes and a mean almond chocolate torte, what mostly stands out from childhood Passover memories is the pleasure of being together with my relatives, not really the food.

Very early into adulthood, I insisted on hosting one of the two seder nights at my house. As I created a family of my own, seder became a significant part of our identity, something we all look forward to every year. And yet, though I had the memory of family togetherness and fun to hold on, I had very few actual food memories.

My challenge was to create my family’s Passover food traditions from scratch, based on cookbooks, stories, and Jewish history. Living in Israel for several years had introduced me to a much wider spectrum of Jewish cooking than what I’d experienced growing up, and on a holiday so focused on our history as a people and our years of wanderings, it seems appropriate to incorporate that history into our food. Today our menu includes the kind of Ashkenazi Passover foods I grew up with, like tzimmes and potato kugel. But in addition, I’ve added other dishes that speak to different periods and places in Jewish history. I created a leek artichoke kugel in homage to the Jewish foods of Italy. This year I’m introducing a savory carrot kugel using baharat, a spice mix used by Jews from Turkey and Iran. We have a Persian-inspired charoset in addition to the apple-based Ashkenazi style. And the last few years I’ve made a salmon dish with garlic and preserved lemon inspired by Jewish Moroccan cuisine. I’m still working on a brisket recipe that uses pomegranate molasses rather than the ketchup flavoring that I grew up with – I made it for the first time last year and I forgot to write it down, so I’ll see if I can recreate it this year.

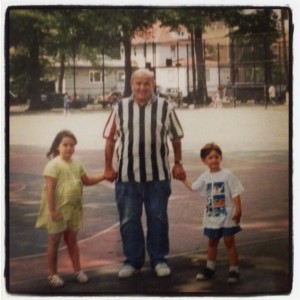

But back to the one exception about my grandmother’s cooking. My grandmother made delicious gefilte fish. That was her annual project. She would come up to New York, and we would trek out to Boro Park to get the fish ground just the way she liked it. The year she kept forgetting if she had salted it, and it came out inedible, was the year we realized something was wrong. That was the last time she made it, and the last year she was able to sit at the table and enjoy the proceedings.

I’d love to say that I picked it up from there, but I didn’t. It’s been many years since I tasted my grandmother’s gefilte fish. Now we have something else entirely new in its place, a tricolor gefilte fish terrine that I learned about from my sister. It’s delicious, lighter and sweeter than my grandmothers and on the sweet side – a real crowd pleaser. My grandmother – who preferred things salty and peppery – would have hated it.

Traditions change. My menu is very different than that of the seders of my childhood. And most of the regulars at our seder are friends, not family, since so few relatives live anywhere near us today. But the excitement about Passover is the same. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that Passover is a major Jewish touchstone in my kids’ lives, even as though go out into the world. We can never fit as many people as we would like around our crowded table so they have to make difficult decisions every year about which friends to invite – the question of who is “Seder-worthy” looms large for them.

Even as Passover is about our history and our legacy, about the passing down of traditions and stories, it is also about ongoing change and evolution. One of our favorite family traditions continues on, the annual miraculous visit of Elijah the Prophet, even though the mantle has now passed on to the third generation. Once the highlight of the seder was the Passover play that my children used to put on for the guests every year. Now, at 20 and 22, they (understandably) refuse to do so, though hopefully our tradition of paper bag dramatics will continue for a while still. As the children have gotten older, the conversations around the table have gotten more involved and deeper. There was the year that one them, in full teenage mode, delivered an articulate and well-reasoned soliloquy about why the divisions of the Four Children was offensive and wrong. In recent years we have related the issue of immigration to Passover. Two years ago we had a special marriage equality reading. This year we are going to read and discuss the Four Children of Climate Change, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s feminist Passover Commentary, among other topics. And there’s of course the orange – a staple on our seder table for many years already at my daughter’s insistence.

My grandmother’s gefilte fish will not be on the menu, but her memory will be on our minds. The tradition keeps changing. Even as we teach about who we were and where we came from, we face the future and keep moving forward.

Tri-color Gefilte Fish Terrine (with thanks to my sister who shared this with me years back)

Tri-color Gefilte Fish Terrine (with thanks to my sister who shared this with me years back)

1 loaf gefilte fish, defrosted

5 carrots, peeled and chopped

1 8-10 oz bag frozen spinach

Boil carrots until soft. Mash in large bowl

Defrost and drain spinach, place in a second large bowl

Divide fish into 4. Place one quarter in bowl with carrots, one quarter in bowl with spinach, and the rest in a third large bowl.

Mix fix and carrots until blended. Mix fish and spinach until blended.

Spray a loaf pan with vegetable spray. Line the bottom of the pan with wax paper and spray the paper. Line the side with wax paper and spray that as well.

Place carrot mixture on the bottom and spread evenly. Place plain fish mixture on top of that and spread evenly. Then spread spinach mix on top and spread evenly.

Spray the top with vegetable oil and place wax paper on top of that. Cover the whole loaf pan tightly with tin foil. Bake at 350 for 1 hour. Cool and then place in refrigerator until ready to serve.

Remove tin foil. Place serving plate over the pan, turn over and let it gently come out of the pan. Peel off the wax paper and slice. Enjoy!