Welcome to His Brother’s Keeper, a fictional mystery series set in 2000, in New York. I’ve decided to periodically lend my blog to a friend, Eva Hirschel. Eva doesn’t have a social media presence but she does have a mystery that she wanted to publish serially on-line, so I’m giving her a hand. (If you’re just tuning in now, I suggest that you start at the beginning). Here is Part I, Chapter 8. Enjoy!

Chapter Eight

Thank God for friends. Was there a prayer for that, I wondered. Sometime during the night, while I was occupied with other matters, Leah e-mailed me the name and phone number of the Reform rabbi in Altoona. She had also given me the name of Altoona’s Conservative congregation and a link to their website. What was even better was that she knew the Reform rabbi, Rabbi Greg Bergman, personally—they had studied together at a rabbinic conference a few years earlier—and she promised that she would call him today and give him the head’s up on my call. Good friends, especially reliable ones, were truly something to be thankful for.

Thank God for friends. Was there a prayer for that, I wondered. Sometime during the night, while I was occupied with other matters, Leah e-mailed me the name and phone number of the Reform rabbi in Altoona. She had also given me the name of Altoona’s Conservative congregation and a link to their website. What was even better was that she knew the Reform rabbi, Rabbi Greg Bergman, personally—they had studied together at a rabbinic conference a few years earlier—and she promised that she would call him today and give him the head’s up on my call. Good friends, especially reliable ones, were truly something to be thankful for.

I was going on a hunch that if Jack Gelberman had really lived in a small city like Altoona, it was likely that he had been a member of a synagogue at one time. That wouldn’t necessarily have been the case in a big city, but small cities without large Jewish populations were different. And since his children and grandchildren seemed to still be Jewish, then the chances were even greater that he had at least belonged to a synagogue when his children were young. Contacting the two local synagogues seemed like a good place to begin gathering information, and might provide useful leads onward.

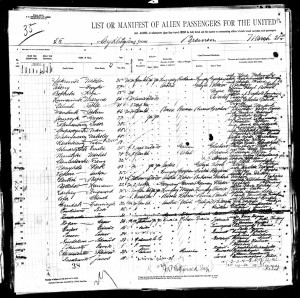

Sometimes genealogical research was like archeology. There were so many layers of sediment to dig through. I’d do hours of research to find out someone’s mother’s maiden name, but that was only in order to get to the next layer, like the mother’s birth certificate or place of birth, or her mother’s maiden name or her parents’ marriage license. Every new bit of information led to another generation, another town, another trail of records. And there were often major roadblocks, especially when I worked for Jewish clients. Countless records were destroyed during the war. And even before the war, there were many inaccuracies and false turns. For example, from as early as the 19th century it had been illegal in Poland not to record a birth. But often people who lived far from registry offices would wait until there were several births to register, so that siblings born years apart would be registered together. The fall of the Soviet Union had been a big boon for genealogists, as previously closed archives were opened to researchers. It was frustrating work, but also exhilarating. Getting that elusive piece of data was a great rush. It was always worth the work.

Occasionally I would promise myself that the next time things were slow, I would research my own family tree. It was crazy that I knew so little about my own family, given the skills and experience I had gained helping other people with theirs. I knew the websites to check, the libraries to visit, the books to read, the agencies to contact, the questions to ask. Yet there was something frightening about beginning the journey toward my own origins. I knew too well the kinds of surprises I stumbled across in other people’s family trees, and I wasn’t sure I was prepared to deal with whatever I might uncover in my own. Most than likely there was nothing—as far as I knew my family was a run-of-the-mill average Jewish American family of Eastern European descent. I had one great-great-great grandfather who had fought in the Civil War, one grandfather who had escaped the Tzar’s army, and one great-grandmother who had been a vocal E.V. Debs and Margaret Sanger supporter. In fact, family legend had it that that same great-grandmother had come to the United States alone at the age of sixteen because she had run away from the marriage her Chasidic father had arranged for her. All of which was interesting, but nothing too out of the ordinary in the annals of American Jewish history. Perhaps my reluctance had more to do with the disappointment I would feel if my family was simply ordinary. One thing I never wanted to be was ordinary, or typical. So I didn’t know which would be worse, to find some horrible surprise in my family tree, or to find none. All in all, better to not even do the research, at least not yet. I didn’t have a free moment to begin, anyway.

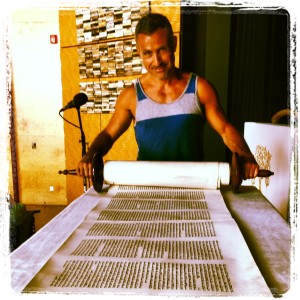

I had promised Hannah that I would take her and Caleb to the library after school, so there was a lot to accomplish in a short time. I got started by tackling one of the books that Rabbi Springer recommended, A History of Chasidism by Rabbi Nissim Rudowsky, filling up index cards with notes and questions. When I put the book down two hours later, my head was swimming with more questions than I had had before beginning to read. Chasidism was a fascinating topic, and I was learning a lot. There was so much I hadn’t understood about the place of Chasidism in Jewish history, and how far back some of the roots of this pietistic movement reached. Nor had I understood how much Chasidism influenced the rest of the Jewish world. Today they were seen, at least by modern, liberal Jews like myself, on the one hand as a quaint, anachronistic, sometimes even embarrassing minority within the Jewish world, an ultra-religious fringe that reminded us of where we might have come from, and just how far we had come. And on the other hand they were seen as a dangerous, threatening group of Jewish fundamentalists with a right-wing political agenda and unethical business practices. But of course, Chasidism was not simply old-time-religion, Jewish style, rather it was a specific expression of Judaism and Jewish spirituality that had its origins in a certain place and time in Jewish history. Today Chasidism seemed removed from the other branches of Judaism being practiced in the United States, and yet so many of the songs we sang in synagogue, the stories we told our children, and the spirituality we sought came out of Chasidism.

The other thing I was learning was about the devastation the Holocaust wreaked on Chasidism. I knew that Jewish life in Poland had been irrevocably destroyed, that a whole world and way of life had vanished. But I hadn’t understood up to now what that meant. Poland had been the central home of Chasidism since it was born in the 18th century. Among the hundreds of thousands of Polish Jews killed in the Holocaust had been a great many Chasidim. Whole dynasties like the Halizchers were wiped out, complete histories were erased and family trees came to abrupt ends. Chasidism had had to be rebuilt, almost from scratch, after the war. The remnants of communities regrouped and rebuilt. Some rabbis had survived, and they gathered followers around themselves once again. Today Chasidism was thriving like it never had before. But the horror and magnitude of what had happened during the Holocaust was overwhelming. It didn’t matter how much I already knew about the Holocaust, how many books I had already read. It was still incomprehensible, beyond the imaginable. And the faith in God and in human beings which so many had continued to show was also incomprehensible. And yet, if Jack Gelberman really was Yankeleh, the Halizcher Rebbe’s grandson, why had he turned his back on his past? Why had he let his grandfather’s followers believe for all these years that he was dead? What had happened to his faith during those terrible years in Europe? And why hadn’t he passed his story on to his children and grandchildren? If I did manage to put together a family tree for him, would it be as great a surprise as Sarah seemed to think it would be, or would he be upset or even angry to have his past dug up? And then back to that important, disturbing question—why did Sarah tell me her grandfather had lived in New York City, and not Altoona?

I lay on the couch, absorbed in thought for some time longer. Finally, I made myself get up. It was eleven o’clock, and I needed to leave in half an hour. It was time to call Altoona.

I asked to speak to Rabbi Bergman , identifying myself as a friend of Rabbi Brown’s, and his secretary put me right through.

Rabbi Bergman , or Steve as he asked me to call him, possessed a deep, melodic voice. I wondered if it was a natural attribute, or a skill he acquired in rabbinic school. I bet no one ever fell asleep during his sermons.

I had a story prepared about why I was doing this research, but at the last minute I decided to just explain the real reason, without going in to too many details. To my great delight, he knew Jack Gelberman.

“I’d be really happy to help you however I could,” Steve said. “It sounds like a nice thing for his granddaughter to want to do for him. But I don’t really know that much about him. And you realize, of course, that what I can tell you depends on what you’re looking for. There are things that would be inappropriate for me to share about a congregant, of course.”

“Yes, sure,” I answered. “Like attorney-client privilege.”

“Something like that,” he said.

“I’m just looking for basic, public-domain kind of information, things that could lead me to other information. Just trying to track down his family tree, nothing sinister or mysterious,” I said, thinking I should have crossed my fingers when I said those last few words. It was hard to lie to a rabbi. “You know, since he came from Europe after the war, it’s hard to find those records.”

Steve cleared his throat. “Look, services start at eight Friday evening. I’ll be at the synagogue from around seven on. Why don’t you come by and we can talk a little bit. If I can help in anyway, I’m more than happy to. Okay?”

Great—eight o’clock services. Caleb and Hannah would be basket cases, and Simon himself would be undoubtedly annoyed. But I said, “Sure, that would be great. I really appreciate it. Um – just one quick question now, to make sure I’m not barking up the wrong tree entirely.”

“Okay.”

“I take it the Jack Gelberman you knew has moved out of Altoona.”

“Yes, that’s right. He retired and moved down to the West Coast of Florida a few years ago.”

Bingo! I took a deep breath, contained myself, and said calmly, “Great, see you Friday then..”

“Okay, good.”

Altoona, here we come. Better remember to check out some books on tape when we were at the library this afternoon. It was going to be a long ride.

***

The Committee didn’t meet on a regular basis, but we tried to get together as a group at least every other month. It was difficult, since everyone had complicated schedules. Some of the Committee members I saw and talked to on a regular basis, like Leah and Bird. Some I rarely saw outside of our get-togethers. But the group had a life of its own, like the whole was greater than the sum of its parts. Individually, we were just a bunch of friends. But as a group, we were something amazing, a tightly knit organism of strong, intelligent, interesting women, as necessary for each of our existences as air and water.

Tonight we were meeting at Bird’s place. Bird was the daughter of former sixties flower children. Her brother was named Cloud and her sister was Sky. Thank goodness they stopped having children before they got to Frog or Grass. Bird and her partner Lydia lived in a spacious, airy, sun-filled loft in a part of Brooklyn known as DUMBO, the area Down Underneath the Manhattan Bridge Overpass. It was a semi-industrial area that was also home to many artists and other urban pioneers. Their loft, decorated eclectically but with great care, had once been part of a thread factory, and its enormous windows offered panoramic views of the Hudson River, the Manhattan Bridge, and the Brooklyn Bridge. Lydia’s collection of Yoruba art was displayed on glass shelves that wrapped around a center supporting column, and their collection of 19th century glass toilet water bottles was arranged around another column. Their many books were arranged alphabetically on bookshelves that covered whatever wall space was not taken up by the windows. All the furniture was either black or a soft, buttery cream. Every book was in its place, and there was no clutter on any visible surface. I knew Bird and Lydia well enough to know that it wasn’t just because there were guests–they really lived like this. Then again, they had no children.

Besides Leah and Bird, the Committee consisted of Meg, a documentary film-maker and professor; Emma, an ob/gyn who was getting married next summer; Claire, who worked in international banking and was pregnant; and Lucy, the director of a center that provided refuge and legal aid to battered women, and who had recently adopted a baby with her partner Amy. With the exception of Lucy, who was living in Northampton, Massachusetts, we had all wound up in the New York area in the last few years.

Bird put out some bowls of chips, salsa, and dips, along with sliced vegetables and freshly prepared endamame. I grabbed a chilled bottle of my favorite beer, Brooklyn Brewery’s Chocolate Stout, and hopped up on a stool. How wonderful to be out in the evening just for fun, not for work, not something connected to the kids, just for myself. It was a treat whenever Simon and I got our acts together enough to go out on a date, but this was something I missed too, getting to go out on my own and see my friends.

As everyone arrived, clusters of conversations sprang up while the Mets and the Yankees slugged it out on the radio in the background. Bird and Leah were both serious baseball fans and had to have the game on. Claire asked me pregnancy questions, and I tried to allay her fears. She looked great, better than I ever did in either of my pregnancies. As a matter of fact, she looked better pregnant than I looked any day. Some people just had all the luck. She was a few inches taller than I, but looked even taller in her orange platform slingbacks. During the day Claire dressed buttoned-down corporate, but after hours she was something else altogether. She was one of those women who could make any crazy old outfit look like a new fashion trend. Her shoulder-length curls were swept up in a loose knot at the top of her head. She wore a tight-fitting orange and gray striped tube dress that showed off her new curves and bulging torso, and silver bangle bracelets. The woman had guts. During both my pregnancies my wardrobe consisted of three choices of black leggings, one pair of blue stretchy overalls, one black jumper and one denim jumper, and an assortment of over-size T-shirts, sweaters, sweatshirts, and Simon’s discarded button-downs.

I couldn’t help ribbing Claire about what her pregnancy was doing to her breasts, which she herself normally described as concave. “You look great in that thing,” I said, “but I know the real reason you’re wearing those tight-fitting outfits, my dear, and it’s not to show off your belly.”

She smiled and wiggled her torso. “Hey, this is the first time I’ve had ‘em, so I might as well flaunt ‘em. Now I know how you girls feel. The only problem is, I can’t get a bra that fits right. I don’t even know what size I am anymore.”

“Yeah, and it keeps changing, too. Wait and see what happens when you start nursing!”

“Well, I’ll need nursing bras, but I need some good bras for now.”

“I’ve got the place for you. You’ve got to come with me to Miss Sylvia’s and meet the ladies. They’re the best fitters around.”

“Name the date and I’m there.”

Soon Bird began to produce an intriguing array of bowls and platters and dishes, and we heaped our plates before moving over to the sitting area. Bird was a great cook, having had to learn to fend for herself at an early age while her parents were otherwise occupied at rallies and sit-ins. She had prepared a do-it-yourself kind of meal that involved tortillas, caramelized red peppers, grilled vegetables, shredded cheese, whole cloves of roasted garlic, refried beans, brown rice, sautéed tofu, and salad, along with various salsas and sauces. The objective was to create your own fantasy vegetarian fajita. It was going to be messy, but delicious.

For some time there was only the sound of slurping, chewing, chomping, and swallowing. One of the things that amazed me when I first got to know this group of women was that no one in the group was afraid to eat. Up until I met them, I had only known women who were scared of food. In high school I learned that it wasn’t feminine to be hungry, finish the food on my plate, ask for seconds or eat with gusto. Instead, mealtimes were battlefields, during which every bite was a possible sabotage of the body-image we were supposed to aspire to in order to be attractive. Until college I hadn’t known that eating disorders were diagnosable and could be treated; I had thought it was simply normal for women to deny themselves food or to binge and purge.

The coffee table filled up with empty plates, and the room began to buzz with conversation. When it was my turn to give an update, I found myself telling them about Sarah Gelberman and my forays into the world of Chasidism.

“Chasidism, of all the things, Abby,” exclaimed Meg. “What’s the pull for you? Sounds like there’s something.”

I answered, “It’s interesting, a whole new world and familiar at the same time. I’m getting a crash course in a slice of Jewish life I know nothing about.”

Bird got in to lawyer mode, ready to challenge me. “What’s familiar about them? Is this some kind of back-to-your-roots thing? What do you have in common with a bunch of Jewish fringe radicals, these sexist racists who have some of the worst business practices when it comes to real estate in New York City.”

Leah, defender of the faith, jumped in. “Whoa, let’s hear it for multicultural sensitivity. Any other thoughts on the subject, Bird?”

Trying not to sound defensive, I said, “Come one, there’s all kinds. Some may be abusive slumlords, but just like in any group most are good people. And they’re not all one group anyway. There’s lots of different groups, and they don’t even all like each other. As for them being sexist, it’s not for me how they live, but you have to see it in context. It’s not sexist, just different.”

“All right, maybe,” conceded Bird. “It would take a lot to convince me there’s anything interesting or worthwhile about Chasids, but okay. I don’t know everything.”

“Just don’t tell your clients that,” Leah said, trying to interject some humor. “Like with any other group, stereotypes are stereotypes, and there are so many misunderstandings. And yeah, what happened in Crown Heights in ’91 brought a lot of ugliness to the surface, but it’s also about two groups, both of whom feel they are beleaguered and no one will cut them a break, trying to survive and even thrive in a small amount of space.”

“Okay, fine. Still, you have to admit there are some extreme aspects to the way they live their lives,” said Emma. “Last weekend a colleague had a Chasidic couple who were doing IVF. Saturday was going to be their day, nothing you can do about that. The commandment to be fruitful and multiply takes precedence over the commandment not to violate the Sabbath. So they got special permission from their rabbi to do the procedure on Shabbat, and they stayed near the office in a hotel Friday night so that they wouldn’t have to violate the Sabbath by driving. Okay, so far, so good. But when it was time to do the procedure, they realized that it wasn’t okay for the doctor to be doing what she had to do, since they knew she was Jewish. So they reached a compromise that the husband was comfortable with—the doctor could do the specialized work that only she could do, but they would ask for the help of a non-Jew sitting in the waiting room, and that person would be the one to turn the lights on and off and press the buttons on the sonogram, and do those kinds of things that constitute work that can’t be done on Shabbat. Well, thank God there was someone in the waiting room who didn’t mind helping. But the whole thing was insane. What they can do, what they can’t do, getting the rabbi’s stamp of approval on everything.”

“Does your practice have a lot of Chasidic patients?” I asked.

“Yes, a good percentage. We’re talking about a group that puts a huge value on being fertile and multiplying. I see women who have had ten, twelve children. Can you imagine? The bigger the family, the better, and the more boys, even better. I’ve had to comfort women who have just given birth to their first child, a girl. And women who have just had their eighth, ninth, or tenth daughter, and still no son. And the worst is when for some reason they are not going to be able to have any more children, and they haven’t yet had a son. You can’t imagine the heartbreak.”

She was right, I really couldn’t imagine it.

“I saw a great documentary recently about them,” said Meg. “ It seems like a nice way to live in a lot of ways, in terms of the way the community takes care of itself. They seem to really support each other and do for each other in all sorts of ways. That’s something few of us experience today, that close sense of community and community support.”

“That’s true,” Emma agreed. “Lord knows we could all use more of that. But it’s a downside too. There’s not a lot of independent decision-making going on, not much room for divergent thinking or behavior. There’s a lot of looking over one’s shoulder. It’s intense social pressure.”

“What about the whole ritual bath thing? How can you justify a belief system in which women and women’s bodies are considered impure?” Bird asked.

Leah waved her hand dismissively. “Don’t buy into that perspective. Mikveh can be a beautiful, empowering thing. It’s not about physical impurity, it’s about ritual impurity. That whole issue is misunderstood. It’s about being re-born and emerging in a new spiritual state. I take people to the mikveh for conversion, or before a wedding, or to mark the end of something significant like chemo, and it’s very moving. As for the issue of monthly mikveh visits after menstruation, I hear that for religious couples having to abstain for a certain amount of time each month is a great aphrodisiac. Judaism isn’t anti-sex. After all, it’s a mitzvah to have sex on Friday nights. The Talmud actually says that women are entitled to be sexually satisfied by their husbands. It’s more about letting women have their own space while their have their periods, having ownership over their bodies and the rhythms of their cycles. That may sound archaic to us, but it’s pretty progressive when you think how long that’s been around.”

Claire laughed. “It sounds like it’s the kind of thing that depends on whether it’s a choice or an imposition. When I don’t want it, I don’t want it, and no one has the right to force me, but when I do, I don’t want some rabbi or priest or politician telling me I can’t. Right? ”

We all nodded.

“That’s the problem with so many of these religious systems, it’s other people telling you what to do,” she continued. “They’re boundary issues, who’s in, who’s out, how much can the system tolerate. Dylan wants to have this baby baptized, but I don’t know, I just can’t pledge my allegiance to the Catholic Church. My parents will be upset if we don’t, but how can I promise to raise this child a Catholic when I’m such a non-believer myself. I have no problem with being spiritual, with God per se, but I have problems with the church.”

Bird said, “Well, sweetheart, I was raised with no religion, and look how I turned out. Scary, huh?”

“You know what our problem is?” Meg asked. “We’re getting too dam old. We’re closer to forty than twenty. I used to be the young prodigy on the Film School faculty, as cool as my students, and now I’m starting feel like their mothers. They’re so young, and hip. I don’t even know what hip is anymore. That’s what’s scary. Who cares about religion, no offense Leah, but what about our lives? Where are we going? How are we getting there?”

“We are not old!” I declared.

“We’re here, that’s where we’re going,” Claire said.

“No complaints,” said Emma. “Though I hope I won’t have a hard time getting pregnant when we finally start trying.”

“Have you ever looked around the video store and seen how many new movies have been made or written or produced or edited by people we went to college with?” said Meg. “It’s getting depressing. I want my one big break before I’m forty.”

“I want to find a publisher for my book. And find a great guy,” said Leah.

“I’m pregnant,” said Bird, and we turned to look at her. “Surprise!” she continued, smiling. “Donor number 376, my lucky number.”

No one said anything for a moment, and then everyone started talking at once, offering congratulations, dispensing advice, and asking for details.

When it was time for dessert, Bird brought out a gorgeous marzipan covered birthday cake full of candles for Meg and Emma, who had birthdays three days apart. We carried the cake, champagne, glasses and some blankets out into the hallway and up a rickety metal staircase to the roof deck. When we were all settled into the various unmatched beach chairs and chaise lounges that Bird and Lydia had scavenged, and wrapped the blankets around ourselves, Bird lit the candles. The lack of streetlights in this industrial neighborhood and the many darkened warehouses made the stars above appear especially bright. The East River looked deep and forbidding at this hour, like it concealed many secrets, but beautiful at the same time. The Manhattan skyline glittered garishly in front of us, rebuking the dark Brooklyn waterfront.

“What a gritty little piece of paradise you’ve got here, huh, Bird?” I said appreciatively.

“Let’s each make a wish,” said Meg, “And see if we can make it come true in the next twelve months. Don’t you think we can have some power over our lives?” She handed each of us a lit candle. “Come on, let’s say our wishes aloud, one by one, so we can help each other make those wishes come true. I’ll go first. I wish to find a distributor for Moon Dance.” She blew out her candle and licked off the marzipan that clung to the bottom. “Go on, you next Emma.”

“Hum.” Emma bit on her lip, thinking. “Okay, I have two wishes. I wish to get through my wedding without destroying my relationship with my mother or Mark’s mother, and I wish to get my article published. Okay, three wishes. To be pregnant by this time next year.”

“Not a bad list. Let’s see,” Claire said. “I wish that by next year at this time I will have gotten the hang of this motherhood thing and will have figured out how to balance it all.”

I laughed. “Good luck.”

“My turn,” said Leah.

“But we know what you wish,” said Meg.

“Maybe I’ll surprise you,” she retorted. “Ha. I wish for peace in the Middle East. The end of hunger. A cure for AIDS.” We laughed. “Well, I do. Okay, and someone to enjoy those good days with.”

“I wish for Lydia to get a big job that’s she bidding for, and I wish to make gobs of money between now and next year, so that I can take time off when the baby is born and not feel guilty or poor,” said Bird.

“You’re not allowed to wish things for other people,” said Meg. “Against the rules. Go again. Though you do get some points for being a better spouse than anyone else here!”

Bird shrugged. “Okay, I’ll admit it. I’m terrified about being pregnant, and I hope everything will be okay for me and for the baby. I hope I’ll be a good mother. I hope I’ve made the right choice. I hope it won’t resent having a test tube for a father.” She blew out her candle.

Everyone looked at me, waiting to hear my wish. “I don’t know,” I said. “Do you ever wonder when your life is really going to start? I feel like I’m just waiting until something really happens, but nothing ever does. I guess I wish for the adrenaline to start pumping again, to feel like I’m doing something important, to feel like what I do matters. You know?”

“Abby, how can you say that? You’re working, you love what you do, and you’re in the motherhood trenches. You’re raising two amazing kids,” Bird said.

“Yeah, but I keep feeling like I’m waiting for my real life to begin. Like I’m all dressed up with nowhere to go. Little things are interesting, sure, and my kids are great, but it’s so contained, so manageable, so safe and routine. No highs, no rushes, just another day.”

“What’s wrong with that?” said Leah. “It sounds pretty great, actually. No high peaks, but no deep valleys either. That’s not a bad thing. You have a lot to be thankful for.”

“Leah, no sermons, please,” I said. “I’m not talking about values or objective reality. I’m talking about how I feel.”

“I know what you mean,” said Emma, “You want to soar.”

“To breathe pure oxygen,” said Bird.

“To star in your own movie,” said Meg.

“To be the heroine of your own life,” said Claire.

I leaned back and looked up at the stars. “To be spectacular.”

[To be continued….]

His Brother’s Keeper is entirely fictional. None of the characters or situations described in this series are based on real people or events. Copyright (c) 2015 by Eva Hirschel.

It was finally time. Shlomo and his husband Shimi had been planning this trip for so long. And they both really needed a vacation. The day of the trip, they were so excited they could hardly wait to board the ship.

It was finally time. Shlomo and his husband Shimi had been planning this trip for so long. And they both really needed a vacation. The day of the trip, they were so excited they could hardly wait to board the ship.