In less than a week I will no longer be the mother of teenagers. A major life phase will be over. Don’t worry – I know full well that I’ll still be doing plenty of parenting for many years to come. I’m sure my own mother would report that she still actively parents. But at least symbolically, it feels like the end of something and the start of a something new.

In less than a week I will no longer be the mother of teenagers. A major life phase will be over. Don’t worry – I know full well that I’ll still be doing plenty of parenting for many years to come. I’m sure my own mother would report that she still actively parents. But at least symbolically, it feels like the end of something and the start of a something new.

These kinds of transitional moments are always opportunities for looking back, and as it happens, a recent encounter provided a further push down reflection road. I recently had the privilege of speaking to a group of rabbinic students. In the course of my presentation, ostensibly about my career path and wisdom gleaned along the way (what a funny thought!), a student asked a question that admittedly caught me off guard, and I’ve been thinking about it since then. It was a totally fair question – no criticism is implied other than self-criticism about how I fumbled an answer.

The question was (in my words, not the student’s): It seems that at first you leaned out, and then you leaned in. And then I was asked to address that.

So here goes.

When I was first making choices about my career, Lean In had not yet been written. There was no such expression then. But we did talk back then about the “mommy track” and I spent a lot of time in my last year of rabbinic school stressing about the idea that in making a choice based on my children’s needs, I was somehow making a choice that was “less than.” I remember actually (and to my great embarrassment) crying to my rabbinic mentor, and also to my work supervisor, because I couldnt figure out how I was going to make it all work. Choosing to not go into congregational work felt like being all dressed up and nowhere to go – like I was somehow wasting my education and letting down the system.

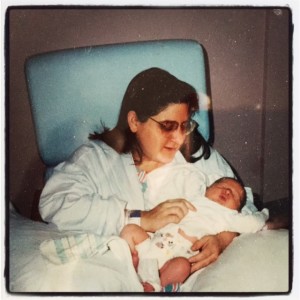

The thing is, I had children before I had a career. I entered rabbinic school (placing out of the first year in Jerusalem and starting as a second year state-side) with a one year old, and became pregnant with my second child in my second semester. So all of my career decisions have centered around the basic fact of being a parent.

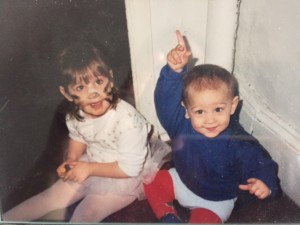

When my classmates in rabbinic school were heading out at the end of the school day to internships, I was heading to the babysitter to pick up my kids. My summers in school weren’t spent doing valuable residency internships or CPE training – I was taking care of toddlers who were too young for day camp.

I have always been a working mother; I was a temple educator when my first baby was born. My first separation from her happened when I went in to work during maternity leave to run teacher orientation – she was ten days old. It was a tough balancing act from the start.

I chose non-congregational work when I was ordained because my children were, at that time, very young. I didn’t want a job that would keep me away from them on weekends and evenings, and where every phone call could be a possible funeral or congregational crisis. But I never chose to not work.

I never chose to not work partly because I always wanted to work – I wanted to contribute to the world and I wanted to use my skills and education in interesting and stimulating ways. Yes, I know that a lot of stay-at-home moms feel that they do that by raising their children. But I knew that that would not be true for me. Moreover, I wanted to share the responsibility of supporting my family financially. I did not want to be financially dependent on a man. And honestly, I couldn’t afford not to work. When I was ordained, my husband was just starting graduate school himself. There was actually no way I couldn’t work.

Yes, I was often jealous of the stay-at-home moms who could socialize with each other during afternoon playdates. I worried that I didn’t go to enough mommy-and-me classes with my children, and that I wasn’t around to go to the park. But I found the best balance I could – working two days a week at home for the first few years, being willing to work often crazy hours and take on an increasingly taxing travel schedule at times so that I could be present for school plays and teacher meetings and basketball games at other times.

Yes, I was often jealous of the stay-at-home moms who could socialize with each other during afternoon playdates. I worried that I didn’t go to enough mommy-and-me classes with my children, and that I wasn’t around to go to the park. But I found the best balance I could – working two days a week at home for the first few years, being willing to work often crazy hours and take on an increasingly taxing travel schedule at times so that I could be present for school plays and teacher meetings and basketball games at other times.

Early on, I formulated a personal give-and-take policy about work, not one for which I sought approval, but one that helped me make it all work. As the job that I initially took because I thought it would provide a good work-life balance began to expand and become huge and insatiably demanding, I made a decision that I would give it my all, but that I would also take what I needed. That is, if I was required to be away for travel and when home, to get back on the computer at night once my kids were in bed, that was ok, but when I had a sick child at home or needed to be present for a visit to the orthodontist or a class presentation, I would not apologize for taking the time I needed for my children. Once they were old enough, I also occasionally took them with me to conferences – if I was required to be away from my family over a weekend, or over a school break, which was often the case, then they could come. They got to ride a mechanical bull at a CCAR conference in Houston during a spring break, they got to throw themselves against a velcro wall at a NATE conference in Kansas City during a winter break, and they helped set up book displays at countless CAJE conferences during summer breaks.

Which is all to say that I don’t think I ever “leaned out.” Not that there’s anything wrong with that choice, but I don’t think that’s a helpful or accurate way to describe the reality of balancing parenting and career. What I did do, in those early years, was find a way to just simply stand up and not collapse. That is, my need and desire to work were in conflict with my need and desire to be a good parent. I found the best imperfect solution possible, one that allowed the insanity of being a working parent to whirl forward.

There was no one magical moment where I suddenly switched from “leaning out” to “leaning in.” My job grew and grew, and then I eventually took a different job that continues to grow, and I continue to love what I do and feel challenged and fulfilled by it. And at the same time, my children grew and grew and their needs and schedules continued to change. Of course there were challenges along the way. Of course there were moments of guilt, and worry. Of course there were moments of realizing the balance was way off, and then recalibrating. Of course there were compromises, some satisfying and some utterly not so, and attendant feelings of frustration or inadequacy. It was never a perfect balance, but it worked. All the various pieces in the constellation of my life somehow held up.

Along the way, the landscape shifted. A year ago my youngest left for college, and this past May my oldest graduated from college and is now herself a member of the work force. So this feels like a moment to both look back and look ahead. From the start of my career, I jumped in with both feet. I was fully committed to my job and its overall mission, even as I was committed to my children. It was never a matter of leaning in or leaning out. Making a career choice based on being a parent is not about leaning out, it’s about finding a workable solution. It doesn’t mean not being fully committed to one’s job, or not being ambitious or driven, it just means that you’re trying to find a healthy balance.

Along the way, the landscape shifted. A year ago my youngest left for college, and this past May my oldest graduated from college and is now herself a member of the work force. So this feels like a moment to both look back and look ahead. From the start of my career, I jumped in with both feet. I was fully committed to my job and its overall mission, even as I was committed to my children. It was never a matter of leaning in or leaning out. Making a career choice based on being a parent is not about leaning out, it’s about finding a workable solution. It doesn’t mean not being fully committed to one’s job, or not being ambitious or driven, it just means that you’re trying to find a healthy balance.

So as someone who is transitioning out of the “working mother” phase, I suggest that we talk about the real underlying issues about women and work, like childcare, equal opportunities, and equal pay. The false polarity between “leaning out” and “leaning in” is one more way that our society expresses its ambivalence about working mothers. It’s one more way that we judge each other. It’s one more way that we hold women to a different standard than men. I just did what I had to do to make it all keep spinning.