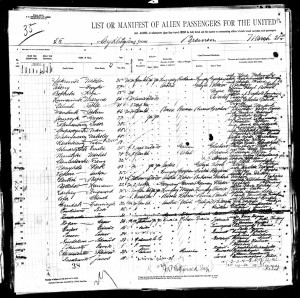

My cousin pointed out the other day it was the 100th anniversary of our grandfather’s arrival to United States, according the ship manifest that he was able to unearth. One hundred years since “our” arrival to this country, at least via that branch of the family tree.

Passover reminds us of the epic journey of leaving a place of suffering in the hopes of finding a better future. “My father was a wandering Aramean,” the haggadah teaches, compelling us to feel as if we ourselves were personally part of the story of leaving and arriving. Jewish history is full of repeated journeys from one place to another, always hoping that things will improve. Mishaneh makom, mishaneh mazal, we’re taught – change your place, and your luck will change. And so they did, over and over.

My grandfather, Louis (Leizer) Person arrived here from Russia, purportedly having escaped the Tzar’s army like so many other Jewish men of his era. He died before I was born and the little I know about him is from snatches of memories from my parents and older cousins. The details of his story are unknown to me but what I do know is that Russia was not a place he wanted to be. It was not a place where he saw a viable future, and he came here to make a fresh start, a modern day Moses. Like so many of his landsmen, he arrived in New York and stayed, eking out a living as a watchmaker.

What I do know is that he and my grandmother, also an immigrant from Russia, had five living children, the youngest of whom was my father. Those children went on to have a total of eleven children, and there are now two more generations after that. From those two immigrants, there are now many descendants spread across the United States.

My grandfather was lucky because he had a place to go, a way to get there, and a route to citizenship once here. He was able to become an American. Though his life, from what I have heard, was difficult, it was nothing compared to what he would have faced if he had stayed in Russia. Because he chose to leave, his children, and then his grandchildren, and all the subsequent generations have opportunities, freedom of religion and ideas, and the chance for a future.

For all the reasons that complicated families have (and whose family isn’t complicated?), I don’t know all of the descendants of my grandparents. But I do know a lot of them. There are still a lot of Persons out there, regardless of the last name they carry.

One hundred years later, who are we? It’s hard to know what my grandparents would have expected or hoped for in their descendants. But what I do know is how very American we have become.

Collectively, we live, I think, in different parts of the United States, with a small concentration in the greater New York area and a large concentration in Florida. We work in a huge range of different professions. As a group, we are Democrats and Republicans and those who choose not to vote. Some of us are fervently for gun control and others are gun owners. Some of us support women’s reproductive rights and some vote for those who don’t. Among us are those who care about animal rights and the legalization of marijuana and the problem of sexual assault on college campuses and the censorship of books and the abuse of children and the right to bear arms.

We are light skinned and dark, our eyes are blue and green and hazel and brown. We are tall and short, slim and athletic, buff from working out, agile from yoga, and always struggling with our weight. We speak, at minimum, English and Spanish and Hebrew with a smattering of Yiddish phrases. Our children’s names are sourced from Yiddish, or modern Hebrew, or the Bible, or Spanish, or English. Some of us have photos on our Facebook pages posed in front of Christmas trees, and others are lighting menorahs or showing off the Seder table, and some have both. Some of us spend Friday nights or Saturdays at synagogue, and some of us spend Sunday mornings in church. Our children go to public schools, private schools, Jewish day school, hebrew schools, and are homeschooled. Some of us have tattoos, some of us have beards, some us shave our heads, some of us don’t shave our legs, some of us shave our chests. We are accountants, long distance truck drivers, artists, grant writers, computer programmers, boat salesmen, antique dealers, a rabbi, retired from the military, homemakers, activists, community organizers, and all kinds of other things. We are gay and straight, married, divorced, and single. We are just about everything Americans can be.

My grandfather was a wandering Aramean. One hundred years ago a young Jewish man left the world he knew, got on a boat, and sailed to New York. He left his family behind, as well as the reality of oppression and violence. He set out on his way, choosing to become a stranger in a strange land. Whatever lay in front of him had to be better than what he was leaving behind. And with him, a new world began, a world that would include my father and his siblings, and all their generations.

Passover reminds us of the obligation of loving the stranger. We were strangers in the Land of Egypt, the Torah teaches. We know what it’s like to be the stranger, to escape hardship and have to start all over again. And if we are lucky, and if we find a welcome and a path to belonging, things may be better – if not for us, then for our children.

During this week of Passover, as we remember having left Egypt, I think about my grandfather’s personal exodus out of Russia. Of my grandfather’s many descendants, no one among us is world famous or has changed history – yet. We are a motley crew (written with great affection and love) whose lives represent a large range of choices and perspectives.

Yet despite our dissimilarities and our different choices about how to live, we are all testaments to survival, and inheritors of a dream. We are Americans because this country opened its doors to our grandfather, and to so many like him. We know what it’s like to be strangers. We owe an enormous debt to our immigrant ancestors that we must pay forward by working toward immigration reform in memory of all the grandparents and great-grandparents and generations back who risked everything and set off into the unknown so that we, their descendants, could have freedom and the right to make choices.

In memory of those for whom America was nothing but a dream, and who perished dreaming, I work with the children of the undocumented and hope to be here – near the workers in the fields – on THAT day – when their dream becomes a reality.

I can not speak Spanish, so I won’t be able to help them with the paperwork, but I will hold their babies, sweep the floors and make coffee… in memory of the grandparents I never knew.

To be a Jew is to be a dreamer… and a toiler in the fields of dreams.